Original Adelaide Football Club

By Peter Cornwall

It was the first football club in South Australia. It was the first to play night football. Adelaide Football Club was a trendsetter that won a premiership as the best football club in the State and also beat powerhouse Victorian club Carlton.

Only this Adelaide Football Club was not the Crows. It didn’t last long, coming and going, reforming then disappearing. But 131 years before the Adelaide Football Club spectacularly kicked off its Australian Football League life with that stunning, unforgettable 86-point hammering of Hawthorn at Football Park in 1991, the first Adelaide club took its wobbly infant steps. Footy would give the young men of the 24-year-old colony, many of whom played cricket in the summer months, winter recreation to keep them fit in the off-season. Outstanding cricketer and local entrepreneur John Acraman was the man credited with initiating the club’s founding in 1860 when a meeting was held in the Globe Inn, Rundle Street.

The morning newspaper The Register later that week followed up: “A number of gentlemen interested in football have for some time been making active preparations for organising a football club in Adelaide. A meeting with that object in view was held at the Globe Inn last night. The chair was occupied by Mr J. B. Spence. So far, 42 names have been handed in for membership. The first game will be played tomorrow on the north park lands.”

There was no such thing as building a squad, training together or working out strategies at team meetings in those days. They were straight into it, The Register noting “there was a large muster both of members and spectators” for the club’s kick-off. Games to start with were what amounted to intra-club clashes, mostly played between members of the club living north and those living south of the River Torrens, with a third squad, known as Collegians, featuring past and present scholars and teachers.

Acraman, who The Chronicle noted in his obituary in 1907 was “practically the father of football here, for he imported five footballs shortly after his arrival in the State (in 1848)”, and Spence were elected captains for the first clash. The game lasted nearly three hours and Araman’s men “were the most active”. Acraman’s team “obtained one or two goals more than their opponents”, according to The Register.

Players from this first Adelaide Football Club could not have looked less like the 21st century Crows. Some wore their white cricket trousers, while others wore heavy pants known as knickerbockers cut off below the knee or tucked into long woollen socks, along with long-sleeved jerseys. And by May 19 the players were showing their true colours as “the respective sides wore for the first time their blue and pink caps”. The caps were an integral part of a footballer’s uniform in those early days, making it easier for spectators to identify which team had the ball as players scrimmaged for it in often difficult, always primitive conditions.

The thrills and spills of this rapidly-developing sport were already making it a game for the fans, with dignitaries including the Governor, the Anglican Bishop of Adelaide, members of parliament, doctors, police inspectors, army captains and the sheriff among growing crowds. A brass band added to the entertainment.

On May 26 there were 40 competitors when the match kicked off but “as the game progressed, that number was increased to nearly 70”. “One and a half hours elapsed before the first goal was made … it was obtained by the Pinks.” The Pinks in this clash were the South Adelaideans, skippered by Acraman. While goals were hard to come by – this game was pronounced a one-all draw as “the shades of the evening came on the players” – the crowd had plenty to cheer about, the hurly-burly resulting in “injured shins, awkward tumbles and other ludicrous mishaps”. The Register’s reporter wrote: “During the game an accident happened to one of the players, Mr George Barclay. It occurred by another, a gentleman on the opposite side running against him, which caused him to fall heavily on the back of his head. He was insensible for a short time, but a little cold water revived him.”

Adelaide’s first recorded match against a rival club was in 1862 against the Modbury Football Club. Adelaide continued its pioneering spirit as it practiced “by moonlight” in 1860, introduced city v country matches in 1864, held the first “Moonlight Football match” between North and South on June 18, 1867 and a decade later was an initiator of intercolonial competition.

A major development in SA football occurred a decade after Adelaide became the State’s first club. The Port Adelaide Football Club was formed in 1870.

Adelaide and Port clashed on the north parklands to kick off the 1871 season and The Register noted: “Victory finally trended towards the city goals, where a general melee ensued, resulting, after a protracted struggle, in a goal for the Adelaideans. The game terminated shortly after 5 o’clock, without another goal being taken.”

Adelaide had initially ruled the roost when it came to the rules adopted by a fledgling sport that was a hybrid of rugby, soccer and Gaelic football, with plenty of its own quirks thrown in. But Full Points Footy’s John Devaney notes the rules of the Kensington club, most heavily influenced by rugby, became the popular choice of clubs in the early 1870s, leaving Adelaide struggling to survive. It stopped playing other clubs in 1873.

Adelaide was not out of action for long. By 1877 the club more than played its part in the formation of the South Australian Football Association, a move that, after years of bickering and uncertainty, finally gave footy the strong structure, the set of rules and regulations, that allowed the game to flourish.

A revolution was afoot that would significantly shape the game of Aussie Rules. On May 7 1877, the Victorian Football Association was formed. Carlton, Melbourne, St Kilda, Hotham and Albert Park were its senior metropolitan clubs and Geelong, Ballarat and Barwon its senior provincial clubs.

But the South Australians had got the jump on the Big V. Adelaide captain Nowell Twopeny was only 19 and had arrived from England just the previous year but his unrestrained enthusiasm and passion for the developing Australian game proved critical. Along with South Adelaide skipper George Kennedy and Woodville captain Joe Osborne, Twopeny put the wheels in motion to form the SAFA. Delegates from 12 SA clubs – Adelaide, Port Adelaide, Willunga, South Park, North Adelaide, Kapunda, Bankers, Gawler, South Adelaide, Victorian, Woodville and Prince Alfred College – met at the Prince Alfred Hotel in the city on April 30, 1877, establishing the governing body that had been so desperately needed, adopting rules in line with Victoria.

In the watershed 1877 season Adelaide, wearing red-and-black striped jersey, stockings and cap, with white knickerbockers, finished third, with 10 wins, three draws and three losses, behind South Adelaide and Victorian. Port Adelaide came fourth, followed by Woodville, South Park, Kensington and Bankers.

Clubs came and went in the SAFA. Norwood joined the Association in 1878 and went on to win the next six flags. Adelaide was very much a part of the merry-go-round that took place, merging with Kensington in 1881 after claiming the wooden spoon, disbanding in ’82 after again coming last, reforming and merging with Adelaide and Suburban Football Association club North Park in 1885.

That year Adelaide again claimed the wooden spoon, albeit in a competition now down to just four clubs, finishing behind premier South Adelaide, Norwood and Port Adelaide. But an advertisement in The Register of Monday, June 29 1885 gave a glimpse into the future – even though it seemed far from a bright future at the time.

The Advertiser on the day of the novel game announced: “Mr. Creswell, the secretary of the South Australian Cricketing Association, has arranged for a football match to be played on the oval this evening by electric light. The contestants will be the Adelaide and South Adelaide clubs. The Military band will be in attendance.”

Fans were expected to be out in force. “There will be sixteen entrances at the front of the oval, and members of the association will be admitted by an entrance at the back of the stand so as to obviate crushing,” The Advertiser said. There were to be six electric lamps, three on each side of the ground.

Unfortunately, the great idea was just too far ahead of its time. The Register the next morning declared the lights “did not sufficiently illuminate the field”. A belt on one of the engines slipped from its wheel in the first half and “for a minute or so that side of the Oval was in darkness”. But the newspaper felt “the undertaking could not be termed a total failure”. While one author of a Letter to the Editor described the game as a “miserable fiasco”, about 8000 people came to have a look – “the pavilion and enclosure were crowded, and round the chains the spectators were very thick, every square inch of the earth mounds also being occupied”. Adelaide also won back in 1885, 1.8 to 0.8. The ball was painted white but it became progressively harder to see as the game wore on because “the colouring on the ball washed off”.

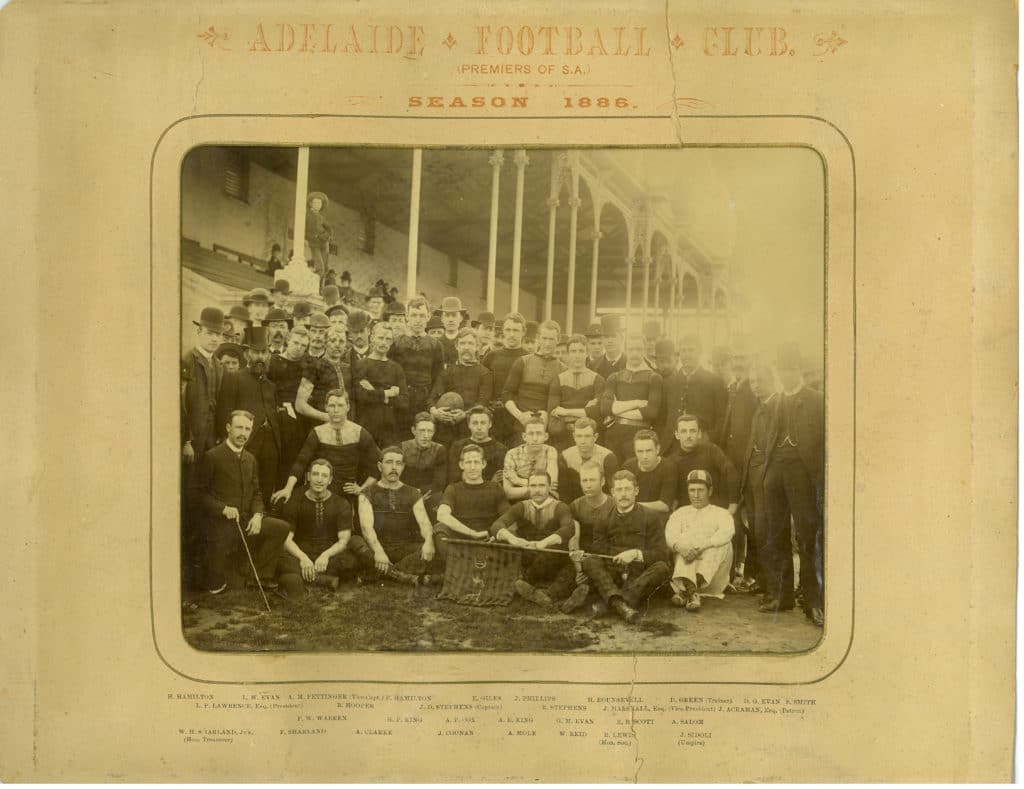

By 1886, Adelaide, under the inspirational leadership of John Stephens and with his brother Richard the standout player, was SA footy’s premier side.

Grand finals did not become a traditional way to decide the premiership until 1898, so Adelaide claimed the flag by being on top of the table at the end of a closely-fought season. Adelaide won nine, lost five and drew one of its 15 matches, South Adelaide had a 7-6-2 record, Norwood was 8-5-2 and Port Adelaide 3-11-1. Norwood dropped from second to third because it was disqualified in one game

The Register’s Goalpost, in his review of the season, noted: “Without an exception the Adelaides are, I believe, South Australians. Nearly all have learnt their football in the colony, and certainly no prominent footballer from the other colonies has been found in their ranks. The success that has attended the Adelaides proves the necessity for good training and the use of the brain in football. The team trained consistently, and the result has been the successive defeat of all the Association clubs.”

Pace was the name of the game for this side as “with one exception they have played no slow men”. Their predominantly long kicking was described as “good” and their marking “excellent”, while John Stephens was described as having “played half-back in the centre” where he “had few superiors in that position”.

Follower in The Chronicle noted: “To their speed they owe to a great extent their present position at the head of the list. It has been their aim all through to increase this advantage, and flyers have at all times been welcomed.”

While leaping for high marks already was becoming a crowd pleaser, formal training was becoming a key for success, The Chronicle’s scribe writing: “As last year, the premiers have been trained by D. Green, who has made the most of the material at his disposal, the team having invariably lasted well despite the pace at which they travelled.” Richard Stephens “stood head and shoulders above his confreres, and it has been frequently asserted by the supporters of rival teams that he won the Adelaides’ matches for them”. With 17 goals Stephens “kicked far and away more goals than any other man in the association”.

A member of Adelaide’s victorious 1886 team was future Australian Test cricket captain Joe Darling. He was just 15, fresh from scoring a then record 252 for Prince Alfred College in the previous summer’s inter-collegiate match against St Peter’s College. In one clash against Port Adelaide, “the Prince Alfred College boy” kicked the first goal after five minutes play. Adelaide won 3.19 to 1.5. Darling went on to play 34 Tests, captaining Australia in 21 of them, winning three series against England. In 1894, Darling played in a premiership with Norwood.

Adelaide finished third in 1887-89 in a seven-team competition but in ’87 it gave South Australia reason to be proud by beating visiting Victorian Football Association side Carlton 9.11 to 3.11. Carlton won the VFA premiership that season. The Register of July 15 noted Richard Stephens “kicked no less than six goals, hit the post twice, and sent the ball between the post once just as the bell rang” in a stunning matchwinning effort. That evening “the Adelaides gave a social to the Carltons at Beach’s Refreshment-rooms. There were about 100 gentlemen present … the meeting was enlivened by numerous songs and recitations”. The club’s president (Mr. L. P. Lawrence) presented Stephens “with the colours of the club mounted in silver as a memento of his goalkicking in the match”.

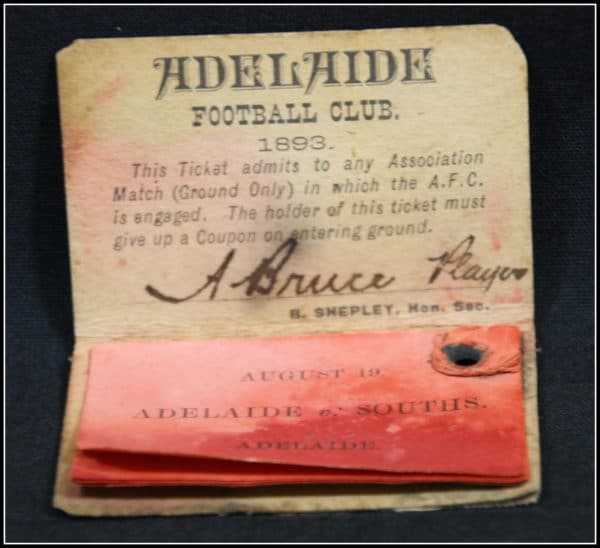

The glory days did not last long. Adelaide’s hot-and-cold history finished with three successive bottom placings, this club’s last hurrah in 1893.

The next time an Adelaide Football Club was to make the headlines was almost a century later, in 1990.